Since I already covered the medieval and Renaissance eras is in my December 4 post todays selections will be from the Baroque, classical and romantic periods.

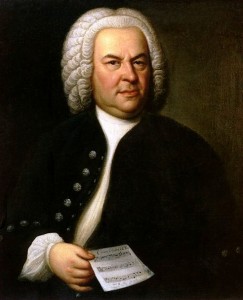

While Handel’s Messiah rightly holds its place as this country’s classical musical soundtrack for the holiday season (quibble if you will about its Easter message; there’s nothing wrong with talking about Easter at Christmas – just ask Bach!), it’s J.S. Bach’s Christmas Oratorio that rings through concert halls throughout Europe at this time of the year.

with talking about Easter at Christmas – just ask Bach!), it’s J.S. Bach’s Christmas Oratorio that rings through concert halls throughout Europe at this time of the year.

The six cantatas that make up the Christmas Oratorio, meant to be performed on six separate days throughout the liturgical Christmas season, tell the Christmas story as only Bach could. With a combination of individual and communal perspective on both the joyful and meditative aspects of the season, it’s a piece that always offers performers the chance to find new perspectives, angles, and ways of expressing eternal thoughts and feelings.

via Bach’s Christmas Oratorio.

Here is part five of the Oratorio

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6-4aOYC8Oys

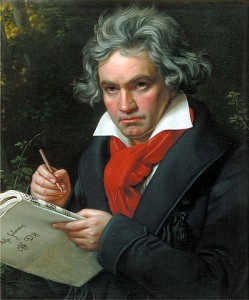

Ode To Joy is the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth and last Symphony. The German composer was increasingly aware of his declining health and spent seven years working on this symphony, starting the work in 1818 and finishing early in 1824. The symphony is one of the best known works of the Western classical repertoire and is considered one of Beethoven’s masterpieces.

of the best known works of the Western classical repertoire and is considered one of Beethoven’s masterpieces.

At the time it was a novel idea to use a chorus and solo voices in a symphony, which is why it’s also called the “Choral” symphony. Beethoven, in fact, had serious misgivings about portraying the music’s message with actual words. Even after the premiere, he apparently came very close to replacing all the vocal lines with instrumental ones.

The words, which are sung by four vocal soloists and a chorus, emanate a strong belief in mankind. They were taken from a poem written by German writer Friedrich Schiller in 1785 and revised in 1803, with additions made by Beethoven.

The Ninth Symphony was premiered on May 7, 1824 in the Kärntnertortheater in Vienna. There had been only two full rehearsals and the performance was rather scrappy. Despite this, the premiere was deemed a great success.

Beethoven was completely deaf when he embarked on this masterpiece, and it’s a tragedy that he never heard a single note of it except inside his head. At the end of the symphony’s first performance the German composer, who had been directing the piece and was consequently facing the orchestra, had to be turned around by the contralto Caroline Unger so that he could see the audience’s ecstatic reaction. Beethoven had been unaware of the tumultuous roars of applause behind him.

via Ode To Joy by Ludwig Van Beethoven Songfacts.

I think Joy is a pretty good word to describe the people in this video.

The Nutcracker (Russian: Щелкунчик, Балет-феерия / Shchelkunchik, Balet-feyeriya; French: Casse-Noisette, ballet-féerie) is a two-act ballet, originally choreographed by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov with a score by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (op. 71). The libretto is adapted from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. It was given its première at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg on Sunday, December 18, 1892, on a double-bill with Tchaikovsky’s opera, Iolanta.[1]

is adapted from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. It was given its première at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg on Sunday, December 18, 1892, on a double-bill with Tchaikovsky’s opera, Iolanta.[1]

Although the original production was not a success, the twenty-minute suite that Tchaikovsky extracted from the ballet was. However, the complete Nutcracker has enjoyed enormous popularity since the late 1960s and is now performed by countless ballet companies, primarily during the Christmas season, especially in the U.S.[2] Major American ballet companies generate around 40 percent of their annual ticket revenues from performances of The Nutcracker.[3][4]

via The Nutcracker – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Those of you with daughters are probably intimately familiar with this piece, as am I. Maybe it even brings back fond memories of your days as a ballerina.

Next Time: Silent Night